In 1990, the U.S. authorities started mailing out envelopes, every containing a presidential letter of apology and a $20,000 test from the Treasury, to greater than 82,000 Japanese People who, throughout World Warfare II, had been robbed of their houses, jobs, and rights, and incarcerated in camps. This effort, which took a decade to finish, stays a uncommon try to make reparations to a gaggle of People harmed by drive of regulation. We all know how some recipients used their cost: The actor George Takei donated his redress test to the Japanese American Nationwide Museum in Los Angeles. A former incarceree named Mae Kanazawa Hara advised an interviewer in 2004 that she purchased an organ for her church in Madison, Wisconsin. Nikki Nojima Louis, a playwright, advised me earlier this yr that she used the cash to pay for residing bills whereas pursuing her doctorate in artistic writing at Florida State College. She was 65 when she determined to return to high school, and the cash enabled her to maneuver throughout the nation from her Seattle dwelling.

However many tales might be misplaced to historical past. My household acquired reparations. My grandfather, Melvin, was 6 when he was imprisoned in Tule Lake, California. So long as I’ve recognized concerning the redress effort, I’ve questioned how he felt about getting a test within the mail many years after the battle. Nobody in my household is aware of how he used the cash. As a result of he died shortly after I used to be born, I by no means had an opportunity to ask.

To my information, nobody has rigorously studied how households spent particular person funds, every price $45,000 in present {dollars}. Densho, a nonprofit specializing in archival historical past of Japanese American incarceration, and the Japanese American Nationwide Museum confirmed my suspicions. After I first began researching what the redress effort did for former incarcerees, the query appeared nearly impudent, as a result of whose enterprise was it however theirs what they did with the cash?

Nonetheless, I believed, following that cash may assist reply a fundamental query: What did reparations imply for the recipients? After I started my reporting, I anticipated former incarcerees and their descendants to talk positively concerning the redress motion. What shocked me was how intimate the expertise turned out to be for thus many. They didn’t simply get a test within the mail; they acquired a few of their dignity and company again. Additionally hanging was how interviewee after interviewee portrayed the financial funds as just one half—although an essential one—of a broader effort at therapeutic.

The importance of reparations turns into all of the extra essential as cities, states, and a few federal lawmakers grapple with whether or not and how one can make amends to different victims of official discrimination—most notably Black People. Though discussions of compensation have existed because the finish of the Civil Warfare, they’ve solely grown in depth and urgency lately, particularly after this journal revealed Ta-Nehisi Coates’s “The Case for Reparations” in 2014. In my dwelling state, California, a activity drive has spent the previous three years finding out what restitution for Black residents would appear like. The duty drive will ship its remaining suggestions—which reportedly embrace direct financial funds and a proper apology to descendants of enslaved individuals—to the state legislature by July 1.

In 1998, as redress for Japanese American incarcerees was winding to a detailed, the College of Hawaii regulation professor Eric Yamamoto wrote, “In each African American reparations publication, in each authorized argument, in nearly each dialogue, the subject of Japanese American redress surfaces. Generally as authorized precedent. Generally as ethical compass. Generally as political information.” Lengthy after it ended, the Japanese American–redress program illustrates how sincere makes an attempt at atonement for unjust losses cascade throughout the many years.

In February 1942, following the assaults on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Govt Order 9066, authorizing the incarceration of greater than 125,000 Japanese People totally on the West Coast. In essentially the most well-known problem to the legality of Roosevelt’s order, Fred Korematsu, an Oakland man who had refused to report for incarceration, appealed his conviction for defying army orders. The Supreme Courtroom upheld Korematsu’s conviction in its now infamous choice Korematsu v. United States. Households like mine had been compelled to desert every part, taking solely what they might carry.

After the battle, many former incarcerees, weighed down with guilt and disgrace, refused to talk about their expertise. However as their youngsters—lots of them third-generation Japanese People—got here of age throughout the civil-rights motion, requires restitution and apology grew inside the neighborhood. In 1980, Congress handed laws establishing a fee to check the difficulty and suggest acceptable treatments. After listening to testimony from greater than 500 Japanese People—lots of whom had been talking of their incarceration for the primary time—the Fee on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians concluded that “race prejudice, battle hysteria and a failure of political management” had been the first motivators for the incarceration. The CWRIC additionally really helpful that $20,000 be paid to every survivor of the camps.

On the identical time, new proof emerged displaying that the federal government had suppressed data and lied about Japanese People being safety threats. Within the Eighties, attorneys reopened the Korematsu case and two related challenges to E.O. 9066. All three convictions had been vacated. By 1988, when reparations laws was making its method via Congress, the authorized proceedings and the CWRIC’s findings supplied the momentum and public proof for Japanese People to make the case for reparations. The 1988 Civil Liberties Act licensed reparations checks to all Japanese American incarcerees who had been alive the day the act was signed into regulation. (If a recipient was deceased on the time of cost, the cash went to their rapid household). The Division of Justice established a particular physique, the Workplace of Redress Administration, to contact and confirm eligible recipients. The CLA additionally supplied for a proper authorities apology and a fund to teach the general public concerning the incarceration: safeguards towards such historical past repeating itself.

Ever since, reparations advocates have invoked Japanese American redress as a precedent that may be replicated for different teams. Dreisen Heath, a reparations advocate and former researcher at Human Rights Watch, advised me Japanese American redress proves that “it’s potential for the U.S. authorities to not solely acknowledge and formally apologize and state its culpability for a criminal offense, but in addition present some sort of compensation.” In 1989, then-Consultant John Conyers launched H.R. 40, a invoice to ascertain a fee to check reparations for Black People. Proponents have reintroduced the invoice many times.

In 2021, because the Home Judiciary Committee ready to vote for the primary time on H.R. 40, the Japanese American social-justice group Tsuru for Solidarity submitted to the panel greater than 300 letters written by former incarcerees and their descendants. The letters described how the reparations course of helped Japanese People, psychologically and materially, in ways in which stretched throughout generations. (Along with drawing on that wealthy supply of knowledge for this story, I additionally interviewed household buddies, members of the Japanese American church that I grew up in, and different former incarcerees and their youngsters.)

In one of many letters, the daughter of an incarceree tells how the $20,000, invested in her household’s dwelling fairness and compounded over time, in the end enabled her to attend Yale. “The redress cash my household acquired has all the time been a tailwind at my again, making every step of the best way a tiny bit simpler,” she wrote. Simply as her household was capable of construct generational fairness, she hoped that Black People, too, would have “the selection to spend money on schooling, homeownership, or no matter else they know will profit their households, and, via the extra selections that wealth offers, to be slightly extra free.”

The redress effort for World Warfare II incarcerees has formed California’s activity drive in extremely private methods. Lisa Holder, an lawyer who sits on the duty drive, first noticed the thought of reparations develop into concrete via her greatest good friend in highschool, whose Japanese American father acquired a cost. The one non-Black member of the duty drive is the civil-rights lawyer Don Tamaki, whose dad and mom had been each incarcerated. Tamaki, like many different individuals I interviewed, acknowledges that incarcerees have totally different histories and experiences from the victims of slavery and Jim Crow—“there’s no equivalence between what Japanese People suffered and what Black individuals have gone via,” he advised me—however he additionally sees some parallels which may inform the reparations debate.

Tamaki’s life, like that of many Japanese People, has been formed by his household’s incarceration. As a younger lawyer, he labored on the authorized crew that reopened Korematsu. Tamaki is now 72. In January, he and I met on the Outlets at Tanforan, a mall constructed atop the land the place his dad and mom, Minoru and Iyo, had been incarcerated. Subsequent to the mall, a newly opened memorial plaza honors the practically 8,000 individuals of Japanese descent who lived there in 1942. Neither Don nor I had beforehand visited the memorial, which occurs to be close to my hometown. In center college, I purchased a gown for a dance occasion on the mall’s JCPenney.

In 1942, Tanforan was an equestrian racetrack. After Roosevelt issued his internment order, horse stalls had been unexpectedly transformed into residing quarters. Minoru, who was in his final yr of pharmacy college, couldn’t attend his graduation ceremony, as a result of he was incarcerated. The college as a substitute rolled up the diploma in a tube addressed to Barrack 80, Apt. 5, Tanforan Meeting Centre, San Bruno, California. “The diploma represents the promise of America,” he advised me. “And the mailing tube which wraps round this promise—the diploma—constrains and restricts it.” Don nonetheless has each.

When the checks arrived within the mail within the ’90s, the Tamakis gathered at Don’s home. His dad and mom spent one test on a brown Mazda MPV, which they might use whereas babysitting their grandkids. They put the opposite test into financial savings. “They didn’t do something extravagant,” Don advised me.

To speak about reparations is to speak about loss: of property and of personhood. In 1983, the CWRIC estimated Japanese American incarcerees’ financial losses at $6 billion, roughly $18 billion right this moment. However these figures don’t seize the desires, alternatives, and dignity that had been taken from individuals throughout the battle. Surviving incarcerees nonetheless really feel these losses deeply.

Mary Tamura, 99, was a resident of Terminal Island off the coast of Los Angeles. “It was like residing in Japan,” she advised me. Together with the island’s 3,000 different Japanese American residents, she celebrated Japanese holidays; realized the artwork of flower arranging, ikebana; and wore kimonos. Then, on December 7, 1941, shortly after Pearl Harbor was attacked, the FBI rounded up males and neighborhood leaders, together with Tamura’s father. Two months later, Terminal Island residents had been ordered to go away inside 48 hours. Tamura, who as soon as dreamed of instructing, as a substitute joined the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps. On Terminal Island, Japanese houses and companies had been razed.

Lily Shibuya was born in 1938 in San Juan Bautista, California. After the battle, her household moved to Mountain View, the place they grew carnations. Shibuya’s older siblings couldn’t afford to go to school and as a substitute began working instantly after they had been launched from one of many camps. Her husband’s relations, additionally flower growers, had been capable of protect their farmland however misplaced the chrysanthemum varieties they’d cultivated.

Shibuya advised me that together with her reparations test, she purchased a funerary area of interest for herself, paid for her daughter’s wedding ceremony, and lined journey bills to attend her son’s medical-school commencement. Tamura used a part of her redress cash for a trip to Europe together with her husband. The opposite funds went towards beauty eyelid surgical procedure. “It was only for magnificence’s sake—vainness,” Tamura advised me.

Many recipients felt moved to make use of the $20,000 funds altruistically. In a 2004 interview with Densho, the then-91-year-old Mae Kanazawa Hara—who’d given an organ to her church—recalled her response to receiving reparations: “I used to be form of surprised. I stated, ‘By golly, I’ve by no means had a test that quantity.’ I believed, Oh, this cash could be very particular.” Some recipients gave their test to their youngsters or grandchildren, feeling that it ought to go towards future generations.

The notion that recipients ought to use their cash for noble functions runs deep within the dialogue about reparations. It helps clarify why some reparations proposals find yourself trying extra like public-policy initiatives than the unrestricted financial funds that Japanese People acquired. For instance, a 2021 initiative in Evanston, Illinois, started offering $25,000 in dwelling repairs or down-payment help to Black residents and their descendants who skilled housing discrimination within the metropolis from 1919 to1969. Florida offers free tuition to state universities for the descendants of Black households within the city of Rosewood who had been victimized throughout a 1923 bloodbath. But when the objective of reparations is to assist restore dignity and alternative, then the recipients want autonomy. Solely they will determine how greatest to spend these funds. (Maybe recognizing this, Evanston’s metropolis council voted earlier this yr to supply direct money funds of $25,000.)

Not each Japanese American whom I interviewed deemed the reparations effort useful or honest. After I arrived at Mary Murakami’s dwelling in Bethesda, Maryland, the 96-year-old invited me to sit down at her dining-room desk, the place she had laid out a number of paperwork in preparation for my go to: her yearbook from the highschool she graduated from whereas incarcerated; a map of the barracks the place she lived in Topaz, Utah; a film poster–measurement copy of Govt Order 9066, discovered by her son-in-law at an vintage store.

She first noticed the order nailed to a phone pole in San Francisco’s Japantown as a excessive schooler, greater than 80 years in the past. A rumor had been circulating in Japantown that youngsters is likely to be separated from their dad and mom. Her mom and father gave every little one a photograph of themselves, so the youngsters would keep in mind who their dad and mom had been. Additionally they revealed a household secret: Atop the best shelf in one in all their closets sat an iron field. The kids had by no means requested about it, and it was too heavy for any of them to take away, Murakami recalled. Contained in the field was an urn containing the ashes of her father’s first spouse, the mom of Murakami’s oldest sister, Lily.

The federal government had advised them to take solely what they might carry. The ashes of a useless girl must be left behind. Murakami and her father buried the field in a cemetery outdoors the town. With no time to or cash to organize a correct tombstone, they caught a selfmade wood marker within the floor. Then they returned dwelling to renew packing. They bought all their furnishings—sufficient to fill seven rooms—for $50.

Murakami’s household, just like the Tamakis, went to Tanforan, after which to Topaz. “Probably the most upsetting factor about camp was the household unity breaking down,” Murakami advised me. “As camp life went on, we didn’t eat with our dad and mom more often than not.” Not that she did a lot consuming—she recollects the meals as inedible, save for the plain peanut-and-apple-butter sandwiches. Immediately, Murakami is not going to eat apple butter or permit it in her home.

After the battle, she did her greatest to maneuver ahead. She graduated from UC Berkeley, the place she met her husband, Raymond. They moved to Washington, D.C., in order that he may attend dental college at Howard College—a traditionally Black college that she and her husband knew would admit Japanese People.

Absent from the paperwork that Murakami saved is the presidential letter of apology. “Each Ray and I threw it away,” she advised me. “We thought it got here too late.” After the battle ended, every incarceree was given $25 and a one-way ticket to go away the camps. For Murakami, cash and an apology would have meant one thing when her household was struggling to renew the life that they’d been compelled to abruptly placed on pause—no more than 40 years later. She and her husband gave a few of their reparations to their youngsters. Raymond donated his remaining funds to constructing the Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism in Washington, D.C., and Mary deposited hers in a retirement fund.

A $20,000 test couldn’t reestablish misplaced flower fields, nor may it resurrect a previously proud and vibrant neighborhood. Nonetheless, the cash, coupled with an official apology, helped alleviate the psychological anguish that many incarcerees endured. Lorraine Bannai, who labored on Fred Korematsu’s authorized crew alongside Don Tamaki, nearly by no means talked together with her dad and mom concerning the incarceration. But, after receiving reparations, her mom confided that she had lived underneath a cloud of guilt for many years, and it had lastly been lifted. “My response was, ‘You weren’t responsible of something. How may you suppose that?’” Bannai advised me. “However on reflection, in fact she would suppose that. She was put behind barbed wire and imprisoned.”

Yamamoto, the regulation professor in Hawaii, stresses that the goals of reparations should not merely to compensate victims however to restore and heal their relationship with society at giant. Kenniss Henry, a nationwide co-chair of the Nationwide Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America, advised me that her personal view of reparations has advanced over time. She sees worth in processes equivalent to neighborhood hearings and stories documenting a state’s historical past of hurt. “It’s essential to have some type of direct cost, however reparations symbolize greater than only a test,” she stated.

The Los Angeles neighborhood organizer Miya Iwataki, who labored towards Japanese American redress as a congressional staffer within the Eighties and now advocates for reparations for Black Californians, sees the checks and apology to World Warfare II incarcerees as important components of a bigger reconciliation. In 2011, Iwataki accompanied her father, Kuwashi, to Washington, D.C., to obtain a Congressional Gold Medal for his World Warfare II army service. All through their journey, he was greeted by strangers who knew of Kuwashi’s unit: the all-Japanese one centesimal Battalion of the 442nd Regimental Fight Group, recognized for being essentially the most adorned unit of its measurement and size of service. Because the Iwatakis settled into their seats on the return flight, Kuwashi advised Miya, “That is the primary time I actually felt like an American.”

For many years, former incarcerees have saved recollections alive, and now that activity falls to their descendants. Pilgrimages to former incarceration websites have resumed because the top of the pandemic, and new memorials, just like the one on the Tanforan mall, proceed to crop up. “The legacy of Japanese American incarceration and redress has but to be written,” Yamamoto advised me.

In January, my mother and I drove to Los Angeles for an appointment on the Japanese American Nationwide Museum. We had been there to see the Ireichō, or the sacred guide of names. The memorial arose out of one other beforehand unanswered query: What number of Japanese People in complete had been incarcerated throughout the battle? For 3 years, the Ireichō’s creator, Duncan Ryūken Williams, labored with volunteers and researchers to compile the primary complete record, with 125,284 names printed on 1,000 pages.

I used to be surprised on the guide’s measurement, and much more moved by the memorial’s design. On the partitions hung wooden panels with the names of every incarceration camp written in Japanese and English, together with a glass vial of soil from every web site. My mother and I had been invited to stamp a blue dot subsequent to the names of our relations, as a bodily marker of remembrance. When the museum docent flipped to my grandfather, Melvin, I used to be reminded that I’ll by no means be capable of ask him what he skilled as a toddler. I’ll by no means be taught what he thought when, in his 50s, he opened his apology letter. The one further element that I realized about him whereas reporting this text was that, in keeping with my grandmother, he mistakenly listed the $20,000 as earnings on his tax return.

However via my conversations with surviving incarcerees, lots of whose names additionally seem within the Ireichō, I may see how a mix of symbolic and materials reparations—cash, an apology, and public-education efforts—was important to a multigenerational therapeutic course of. For Melvin, a third-generation Japanese American, this may need seemed like receiving the test. For me, within the fifth technology, inserting a stamp subsequent to his title helped me honor him and see his life as a part of a a lot bigger story. The challenge of constructing amends for Japanese American incarceration didn’t finish with the distribution of redress checks and an apology. It may not even end inside one lifetime, however every technology nonetheless strives to maneuver nearer.

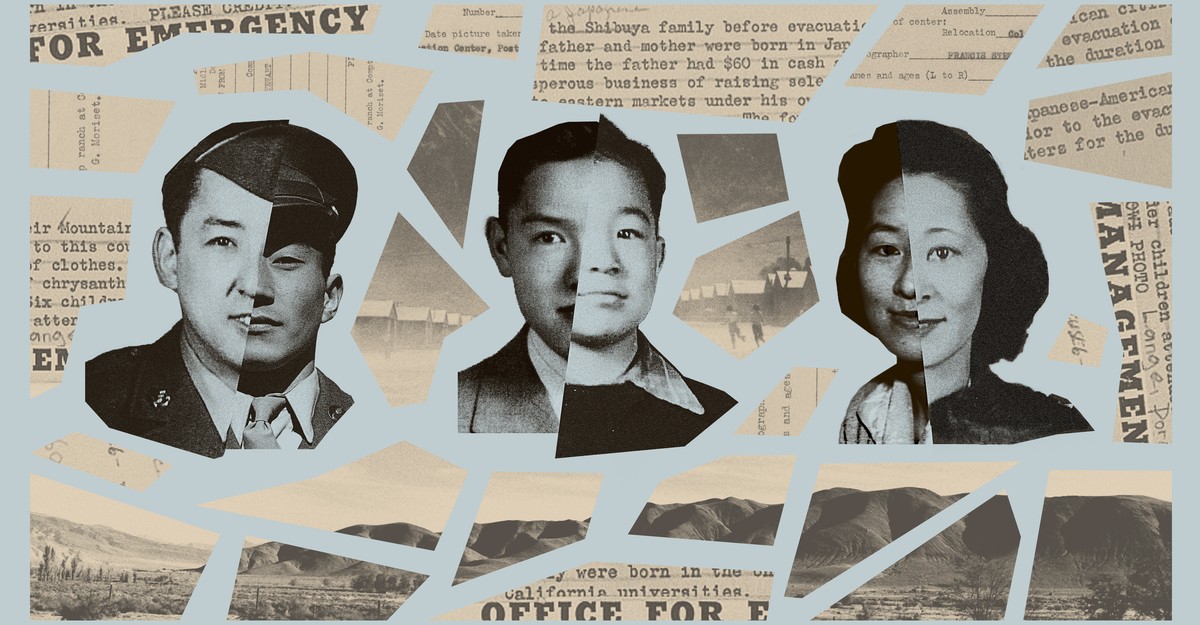

Photograph-illustration sources: Buyenlarge / Getty; Corbis / Getty; Dorothea Lange / U.S. Warfare Relocation Authority / Getty; Historical past / Common Photos Group / Getty; Library of Congress; Stephen Osman / Getty; Bancroft Library / UC Berkeley